The Commedia is Dante’s most famous work. Known and studied worldwide, it is considered one of the greatest masterpieces of world literature of all time.

Dante’s Commedia is a poem composed, according to critics, between 1307 and 1321. I will open a parenthesis here to point out that the adjective Divine, commonly used in the title of this work, was attributed by Boccaccio and not by the author, and only appeared starting with the printed edition of 1555. The entire world associates this poem with fiction, with a brilliant imagination, or with historical facts. Every student of universal Gnosticism must know that this account is not imaginary in the least. On the contrary, poetry was skillfully used by Durante degli Alighieri, known as “Dante”, to recount his conscious descent into the Infernal Worlds of the Earth. The conscious descent into hell is a natural process that every Initiate must experience. To study this subject in depth, read The Three Mountains and Yes, There is Hell, the Devil, Karma by Samael Aun Weor.

The choice of translation

There are many French translations of the Commedia, and it was with the concern of making available a version that respects the original as closely as possible that I conducted research and compared more than a dozen translations. I first settled on the translation by Ernest De Laminne dating from 1913 and 1914, however, I was disappointed to find that only the first two volumes were available. The third, Paradiso, was nowhere to be found and may never even have been published… But luckily, I came across the surprising translation by Madame Lucienne Portier.

French translation by Lucienne PORTIER (1894–1996)

“Another translation of the Commedia! one might say. Yes, yet another translation of Dante’s untranslatable poem. Precisely because it is untranslatable, it requires different approaches.

The guilt of the traitor — traduttore traditore — does not inevitably accompany the translator who, on the other hand, cannot avoid a kind of despair, especially when it comes to poetry — that poetry which resides in the irreplaceable expression where nothing, absolutely nothing can be altered, and whose translation proposes to change the words, syntax, rhythm, sounds… The meaning remains, but the nuances of meaning are so closely tied to the suggestive forms that one again faces a difficulty often insurmountable. One must choose, nonetheless.

After two rejections — rejection of a prose rendering of Dante’s verse which would annihilate it, rejection of a verse translation which might please the ear but inevitably leads to inaccuracies and even mistranslations — my choice remains the stanza, whose rhythm is sought in a harmony as close as possible to the original, without sacrificing important nuances of meaning. Given the impossibility already declared by Dante — ‘no work harmonized by musical linkage can be transformed from its language into another without losing all sweetness and harmony’ (Convivio, I, vii, 14) — one must transmit what can be transmitted. Among what can be transmitted, there is sometimes a certain obscurity, of mystery or reserve, that must not be destroyed by an importunate and grammatically correct clarity.”

Lucienne PORTIER

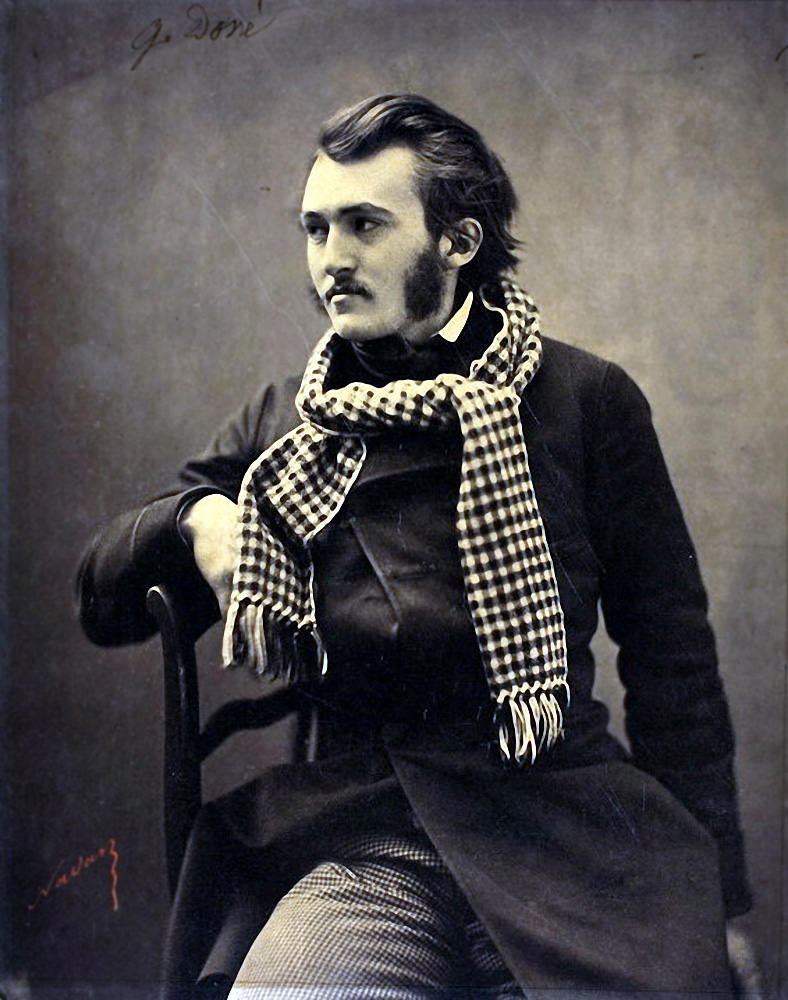

Illustrations by Paul Gustave Doré (1832–1883)

Gustave Doré was a French illustrator, engraver, painter, and sculptor, born in Strasbourg on January 6, 1832, and died on January 23, 1883, in Paris at his hotel on Rue Saint-Dominique. He was internationally recognized during his lifetime.

From 1861 to 1868, he illustrated Dante’s Commedia. Increasingly renowned, both self-taught and exuberant, Gustave Doré illustrated over 120 volumes between 1852 and 1883, published in France, but also in England, Germany, and Russia.

He died of a heart attack at the age of 51 on January 23, 1883, leaving behind an immense body of work comprising over ten thousand pieces, which would go on to exert a strong influence on many illustrators.